When Smart City Mobility Meets Social Inclusion: What Shared E-Scooters Really Deliver

Shared e-scooters have become a familiar sight in many Swiss cities. They are often presented as smart, flexible last-mile solutions that complement public transport and support sustainable urban mobility. But do they actually contribute to socially sustainable mobility, or do they mainly benefit specific user groups?

This Master’s thesis explores this question using the city of Frauenfeld as a case study. The focus lies on how Smart City strategies and digital tools influence the integration of shared e-scooters and what this means for accessibility, inclusion, and last-mile mobility in practice.

How the study was conducted

The thesis is based on a qualitative research design. In addition to a structured literature review, semi-structured interviews were conducted with municipal and cantonal officials, mobility experts, and service providers. The interviews were analyzed using thematic coding to better understand governance practices, stakeholder perspectives, and the role of digital tools in shared micromobility.

This approach allows insights into how shared e-scooters are governed in practice and how social sustainability is addressed, or neglected within Smart City mobility strategies.

Key findings: efficiency first, inclusion second

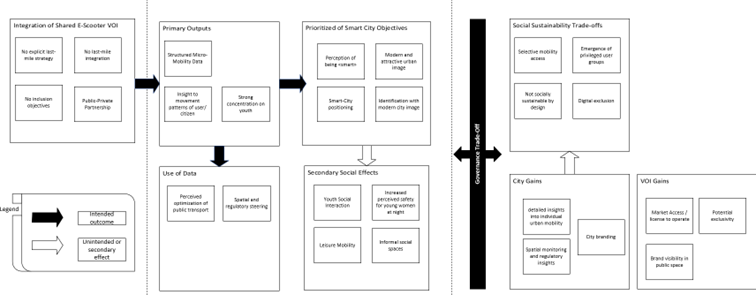

The results show that shared e-scooters in Frauenfeld are mainly integrated through data-driven and reactive Smart City governance. Digital tools are primarily used to monitor usage patterns, regulate public space, and support the city’s Smart City positioning. This governance approach brings clear benefits, such as operational efficiency and valuable mobility data.

However, the study finds that social sustainability is not actively designed. Instead, access to shared e-scooters remains selective. Younger and digitally skilled users benefit most, especially for flexible, leisure-oriented trips and perceived safety in the evening. In contrast, older adults, people with limited digital skills, and people with disabilities face barriers due to app-based access requirements and the lack of alternative usage options.

Importantly, these exclusion risks are widely recognized by local actors but are largely accepted as side effects rather than addressed through targeted governance measures.

A governance trade-off

Based on the empirical findings, the thesis develops a governance trade-off model. The model shows that Smart City ambitions, data-driven steering, and public–private governance arrangements generate operational and symbolic benefits for cities and providers, while social inclusion remains weakly embedded.

Social sustainability does not fail because of technology itself. Instead, it depends on whether inclusion is defined as an explicit governance objective.

What this means for practice

For municipalities, the findings highlight an important opportunity. Digital tools could do much more to support inclusive last-mile mobility if they were used deliberately to reduce access barriers. Clear social inclusion objectives, inclusive last-mile strategies, and alternative access options beyond smartphone apps could help broaden the user base and strengthen social sustainability.

Shared e-scooters can contribute to sustainable urban mobility—but only if Smart City innovation is combined with active and inclusive governance.